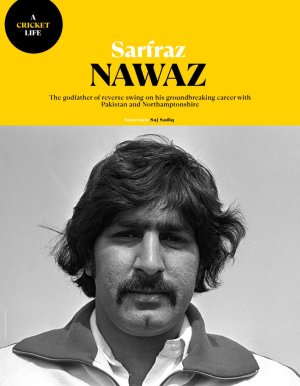

Street smarts

My introduction to cricket was through luck rather than any proper plan or formal route. The plan always was to complete my education, to become an Engineer and then help in the family’s construction business. I went to college, but I struggled with studies and so my father gave me a role within the family business and put me in charge of some construction contracts in Lahore. However, when the Indo-Pak war broke out in 1965 a lot of the work ceased and instead people particularly students from Government College in Lahore would turn up near the construction site and play cricket. I had previously only played street cricket with a tennis ball, so I would just watch the students, labourers and others play, but eventually I joined in as there was really nothing else to do. After playing a few matches in the local park and impressing, I went for trials for the Government College Lahore team and I was selected as a fast-bowler.

Khan Mohammad, Fazal Mahmood and Mahmood Hussain as role models

Back in my day the likes of Khan Mohammad, Fazal Mahmood and Mahmood Hussain were the role-models for upcoming pace-bowlers in Pakistan. There was no televised cricket and if you wanted to see your heroes in action, you had to go to the ground and watch them. I recall the first ever match I saw live was a Test match against West Indies in Lahore in 1959. I remember the excitement and buzz of the occasion and thinking I want to be a part of this in future. Going to watch that match really instilled a desire in me to want to be an international cricketer and one day hear the crowd shouting my name and cheering me on one day.

Early sighter

I made my Test debut in 1969 in Karachi against England but it was a very forgettable match for me. I took no wickets and didn’t get the chance to bat. The next time I played for Pakistan was not until 1972, but never for a moment did I feel that I wouldn’t play for my country again. I had suffered a back injury and whilst injured I had also been working on the art of reverse-swing, so I knew that sooner or later my chance would come. The Pakistan team had Saleem Altaf and Asif Masood as the opening bowlers and I knew that I was a better bowler than them as they had no clue about reverse-swing. My biggest asset was my stamina and strength as a bowler and if the captain wanted me to bowl all day, I could do that.

Education in the shires

Playing in County cricket for Northamptonshire really helped in my development as a person and as a cricketer. My first season there was on a trial basis where they said to me that they would only offer me a contract if I did well during the season long trial. The first season went well for me, but in 1971 I suffered a serious back injury when I was touring England with the Pakistan side. At that point in my career, I was unsure whether I would be able to continue playing cricket as the pain was so intense and I actually thought I was done as a cricketer. I went to see a specialist who advised me complete rest and then said that when making a comeback it should only be at club level and that I should take things lightly. So, in 1972/73 I played in the Lancashire League for Nelson and played the occasional game for Northamptonshire 2nd XI. Then in 1974 after proving my fitness I was offered a full-time contract by Northamptonshire. I played there until 1982, and I recall that time as a fantastic period for my development, especially due to the different surfaces and weather conditions I experienced as an overseas cricketer and having to deal with some great people in the club such as Ken Turner in the secretary’s office. But if there was one person who I learnt a lot from during my career it has to be John Dye who I quite often shared the new ball with at Northamptonshire. He was the bowler who guided me and helped me a lot during my County career and a great support for me in all aspects of my game.

Voyage of discovery

Back in the early part of my career, there were some pitches that were matting wickets, whilst others were turf. I remember that some of the matches I played in were at Minto Park in Lahore which was a matting surface. My deliveries would naturally swing in at this ground more than at grounds which were turf surfaces which fascinated me and I wanted to get to the bottom of why this was occurring. I was always someone who as a bowler liked to experiment and try out different things, so I had been working on shining the old ball and making one side of the ball heavier using saliva and sweat. I also experimented on bowling into the wind or with the wind using the ball that I had been preparing. I realised that for reverse-swing to work, it was better if you bowled into the wind. At that time, I didn’t know the science of reverse-swing, but I knew how to achieve it. The more I experimented, the better I got at it and of course over the course of time, more and more bowlers learnt and perfected the art which was very pleasing, especially given that some felt it was cheating, which of course was never the case.

The greatest spell

Some of the Australian players were missing in 1979 due to the Kerry Packer World Series but they were still a very strong side especially at home. They were well on course to chase down a target of 382 at the MCG in the 1st Test, having been 305 for 3 with Allan Border and Kim Hughes firmly in control and it looked like the match would be over by Tea on the final day. I went up to our skipper Mushtaq Mohammad and said to him to let me bowl as the ball was old and I might be able to do something with it and if I can’t then at least I’ll bowl from a full run-up and slow the over-rate down and maybe get us a draw. We never had victory on our minds, we were just contemplating slowing the over-rate down and escaping with a draw. At the start of the spell, I got a wicket and then it all just went crazy as wicket after wicket fell and before we knew it, we were celebrating an improbable victory. What was really funny was that during the drinks break, Majid Khan had said to me, ‘Sarfraz come on take all 10 wickets’, just to wind Imran Khan up as they weren’t on speaking terms. As far as I was concerned, I was so immersed in the occasion and the match that I had no idea that I had taken 7 for 1 in the space of 33 balls until after the match.

The toxic Pakistan dressing room

I’ve read many times about how the Pakistan dressing room was a toxic place back in my day, but it was nothing of the sort. There were some big personalities in the dressing-room, but we all had experience of County cricket and the professionalism that came with it and we all knew our role within the team. There was some professional and family jealousy but at the same time there was maturity as we knew that we all couldn’t perform every day and that the team came first. These were traits that many of us learnt during our County stints and we knew from County cricket that there would be good days and bad days and we brought that environment into the Pakistan dressing room too.

Presidential approval

Ahead of the 1978 Test series against India, President Zia-ul-Haq hosted a reception for the Pakistan squad at which he announced that there will be awards for the best batsman and best bowler of the series. I said to him, mark my words that the best bowler award will be mine. I don’t think my co-bowlers were impressed with what I had to say, but I achieved what I said I would when I took 17 wickets in the 3-match series. I especially recall the final match of the series in Karachi, when India were comfortably placed on the final day of the Test. I had a chat with my team-mates and said that we can still win the match such was my self-belief. I said to my skipper Mushtaq Mohammad give me the new ball which was due, and I’ll give it my all and put in one last effort. I managed to take 5 wickets in the second innings and we reached 164/2 from only 24 or so overs to win the match by 8 wickets. That was one of my most memorable matches and a match that I look back with fond memories.

Flash Gordon

I faced some of the greatest batsmen in the history of the game. These were names that are legends, names that are top of the list of their respective countries when it came to batting, but the one batsman who was better than the rest was the West Indian Gordon Greenidge. He had a solid defence and his attacking stroke-play was second to none. He was an intelligent batsman who had that knack of working out bowlers pretty quickly. You had to be on top of your game to get the better of him.

Grave threats

The fastest bowlers I faced were Dennis Lillee and Jeff Thomson. I remember walking into bat to face Lillee at Perth during a tour match, back in the day when it was a lightning quick pitch. They used to arrange for touring sides to play at Perth to soften us up and quite often it worked. I walked out to a few verbals from the Australian players and got hit on the glove the very first ball that I faced. I hadn’t faced bowling so quick in my career and did not see the ball at all. Thankfully my batting partner called me for a run after the ball had smashed into my gloves. I had no clue where the ball was but knew that I would be safer at the non-striker’s end so just ran for my life.

Funeral director for Thommo

Jeff Thomson was never short of advice to anyone and everyone and I remember I came up against him in a tour match when he was part of the touring Australia side against Northamptonshire. We bowled hostile spells to each other, bowled bouncer after bouncer to each other and we really took each other on. We didn’t back down and there was a verbal exchange between the two of us which I still remember. I was bowling to him and I said “Look Thommo, I’ve spoken to a funeral director in Northampton and I have asked him to dig a grave for you because I am going to send you there today. I bowled a huge no-ball deliberately which whistled past his nose. The next ball I bowled another short ball which hit his glove and was heading to gully. I shouted to my team-mate David Steele don’t catch it as he is still alive and the funeral director is still waiting for him. I always enjoyed verbal exchanges and getting under the skin of the opposition and never feared any opponent.

The one that got away

My biggest regret when it comes to my playing days may surprise some people but it is losing the NatWest Trophy Final in 1981 at Lord’s against Derbyshire when the scores finished level but we had lost more wickets. I knew the opposition batsmen well but allowed myself to be talked out of setting the fields I wanted by our skipper Geoff Cook and I lost my composure and leaked a few costly runs at the end. To this day I look back at that match as one that got away. Losing any match is painful, but to lose it at Lord’s and in the way we did really hurt.

The cult of Imran

I always felt that Imran Khan initially came into the Pakistan team in 1971 due to his connections within Pakistan cricket rather than on merit. I remember watching his first over for Pakistan which was an 11-ball over and thinking what on earth is going on and why has this guy been selected. But then when he came back to the Pakistan team in 1974, he was a different cricketer. He was mature, he had been working very hard on all areas of his game and you could tell straight away that he was a different cricketer to the raw bowler we saw 3 years earlier. I always believed that he wasn’t a talented cricketer, rather he became a great cricketer through sheer hard work. Whilst he won’t admit it, I felt that he always wanted to be Prime-Minister of Pakistan one day.

Cloud of suspicion

I have always been a strong advocate against fixing in cricket and will continue to speak out about it, despite some people wanting to shut me up regarding this issue. Over the years I have suspected so many matches and periods of play that have been suspicious. Even recently I was watching a tournament where some matches looked extremely suspicious and strange. I don’t feel the cricket authorities have done enough to stamp out corruption, and if this issue is not dealt with, then it will continue to ruin cricket. The International Cricket Council need to go after the big fish rather than concentrating on those involved with fixing who are the small players.

Trying hand at politics

I tried my hand at politics and was elected as a member of the Provincial Assembly of Punjab as an independent candidate in the 1985 Pakistani general election. Given the state of politics around the world these days, maybe I should have continued in politics. I have been an advisor to several Pakistani Governments over the years and served on various Sport’s Boards too. But I wasn’t really interested in politics at all. In fact, when I was vice-captain, I was offered the Pakistani captaincy but didn’t want to get involved in the politics of the job as I was quite happy enjoying life without the pressure and added responsibility of captaincy and instead, I recommended Imran Khan to take over as skipper.

Coaching Shoaib Akhtar and Abdul Razzaq

Once my playing days were over, I didn’t really want to coach full time as the family construction business was the priority. However, I have from time to time helped the Pakistan Cricket Board with coaching stints working with fast-bowlers such as Shoaib Akhtar, Azhar Mahmood and Abdul Razzaq on aspects of their run-up, bowling action, their strengthening and stamina. As far as I am concerned, all year-round coaching is a gimmick and a waste of money. These full-time bowling coaches are appointed in the modern game and it’s a joke because more often than not the best way to coach fast-bowlers is short, sharp coaching days where they are told about the importance of being physically fit and strong and advised on technical aspects such as the run-up, the delivery stride and the follow-through. Fast-bowling isn’t rocket science, but you have to be strong, fit and prepared to put in the work. Any fast-bowlers that need coaching all year and need full-time coaches around them are not going to succeed at the highest level and some of these modern-day bowling coaches just talk a lot of hot air.

Knowing what it took to become a successful bowler

Modern-day bowling has changed a lot since my day. I could bowl all day if needed and then at the end of play do 20 laps of the ground. I didn’t have science or technology to back me or a team of coaches and backroom staff, but I knew what it took to be a successful fast bowler and I knew what I had to get right and what I had to improve upon. I was a quick learner who didn’t rely on others to spoon feed me, rather I learnt a lot by experimenting, with reverse-swing being an example of this. I understood a lot about fast-bowling by watching others, listening to them, talking about pace-bowling. What I didn’t need to improve were coaching manuals or people standing over me and pointing things out to me every day. Nowadays many pace-bowlers lack stamina and want the easy option of making money by playing in Twenty20 leagues around the world rather than playing the beautiful game of Test cricket. They have technical flaws that are overlooked and then people wonder why their careers are cut short.

The legacy

How will I be remembered as a cricketer? Well, I was the bowler with the funny run-up who everyone thought was a medium-pacer, but I knew that I could bowl as quick as anyone when I wanted to. With the bat, I wasn’t the most pleasing on the eye lower down the order, but I could always be relied upon to score some vital runs. I look back on my career with great pride, as a pioneer of reverse-swing and someone who was a part of Pakistan teams that the world admired and respected. I know that I always gave 100% for every team that I played for every single day and as a cricketer you cannot do more than that.