For decades, Pakistan cricket has been synonymous with world-class fast bowling. Our identity, our edge, and often our ticket to glory — bowling has always been the heartbeat of Pakistani cricket. Whether it was the magical swing of Wasim Akram, the reverse-swing mastery of Waqar Younis, or the raw pace of Shoaib Akhtar — these names struck fear into the hearts of batting line-ups around the world.

Growing up, it was normal to see Wasim, Waqar, and Shoaib terrorize even the best in the world. The legacy continued, albeit in a slightly diluted form, with the likes of Mohammad Sami, Shabbir Ahmed, Umer Gul and Shoaib Akhtar carrying the fast-bowling flag. Later, names like Rana Naved, Mohammad Asif, and a young Mohammad Amir brought back glimpses of that lost dominance. Amir, in particular, felt like a breath of fresh air — a generational talent who, despite not fully living up to expectations, had the ability to turn a game on its head.

Even during transitional phases, we were never completely out of decent bowling options. Bowlers like Junaid Khan, Mohammad Irfan, Wahab Riaz, and Sohail Khan — though not at the level of their predecessors — formed a respectable attack. It may not have been the best in the world, but it was still far better than what we are currently seeing.

Today, Pakistan's bowling reserves look alarmingly thin. There is a lack of bite, skill, and — most worryingly — hunger.

A few years ago, there was genuine excitement around Shaheen Shah Afridi and Naseem Shah. Both had pace, potential, and the right attitude. Yet, in 2025, that excitement has turned into concern. Shaheen has lost the swing and sharpness that once made him unplayable in early overs. Naseem Shah, once seen as a prodigy, now looks alarmingly average — unfit, inconsistent, and missing that X-factor.

The situation in the spin department is even more dire. Once boasting greats like Saqlain Mushtaq, Mushtaq Ahmed, Danish Kaneria, and later Saeed Ajmal and Yasir Shah, Pakistan has always had match-winning spinners in the mix. Now, the cupboard is almost bare. There is no clear all-format spinner who can lead the attack or trouble top-tier batters consistently.

This is perhaps the lowest point in terms of bowling depth in Pakistan's cricketing history.

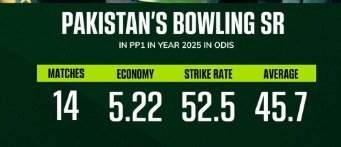

Gone are the days when any one of our bowlers could flip a match on its head. Even on bowler-friendly pitches, Pakistan’s current crop struggles to make an impact. The pace is down, the swing is missing, and there’s no fire in the belly. Watching Pakistani bowlers used to be an event — now, it feels like a chore.

So the question must be asked: Is it time to look ahead and move on from the current lot? Should we begin investing in the likes of Khurram Shahzad, Akif Javed, Ubaid Shah, and Ali Raza? They may not be the finished product yet, but at least they bring energy and ambition — qualities currently missing in the national attack.

The bowling crisis won’t solve itself. Talent needs to be scouted, nurtured, and backed. If Pakistan is to reclaim its legacy as the home of world-class fast bowling, it must start now. The golden era may be over, but there is still time to write a new chapter — if the right decisions are made.

Growing up, it was normal to see Wasim, Waqar, and Shoaib terrorize even the best in the world. The legacy continued, albeit in a slightly diluted form, with the likes of Mohammad Sami, Shabbir Ahmed, Umer Gul and Shoaib Akhtar carrying the fast-bowling flag. Later, names like Rana Naved, Mohammad Asif, and a young Mohammad Amir brought back glimpses of that lost dominance. Amir, in particular, felt like a breath of fresh air — a generational talent who, despite not fully living up to expectations, had the ability to turn a game on its head.

Even during transitional phases, we were never completely out of decent bowling options. Bowlers like Junaid Khan, Mohammad Irfan, Wahab Riaz, and Sohail Khan — though not at the level of their predecessors — formed a respectable attack. It may not have been the best in the world, but it was still far better than what we are currently seeing.

Today, Pakistan's bowling reserves look alarmingly thin. There is a lack of bite, skill, and — most worryingly — hunger.

A few years ago, there was genuine excitement around Shaheen Shah Afridi and Naseem Shah. Both had pace, potential, and the right attitude. Yet, in 2025, that excitement has turned into concern. Shaheen has lost the swing and sharpness that once made him unplayable in early overs. Naseem Shah, once seen as a prodigy, now looks alarmingly average — unfit, inconsistent, and missing that X-factor.

The situation in the spin department is even more dire. Once boasting greats like Saqlain Mushtaq, Mushtaq Ahmed, Danish Kaneria, and later Saeed Ajmal and Yasir Shah, Pakistan has always had match-winning spinners in the mix. Now, the cupboard is almost bare. There is no clear all-format spinner who can lead the attack or trouble top-tier batters consistently.

This is perhaps the lowest point in terms of bowling depth in Pakistan's cricketing history.

Gone are the days when any one of our bowlers could flip a match on its head. Even on bowler-friendly pitches, Pakistan’s current crop struggles to make an impact. The pace is down, the swing is missing, and there’s no fire in the belly. Watching Pakistani bowlers used to be an event — now, it feels like a chore.

So the question must be asked: Is it time to look ahead and move on from the current lot? Should we begin investing in the likes of Khurram Shahzad, Akif Javed, Ubaid Shah, and Ali Raza? They may not be the finished product yet, but at least they bring energy and ambition — qualities currently missing in the national attack.

The bowling crisis won’t solve itself. Talent needs to be scouted, nurtured, and backed. If Pakistan is to reclaim its legacy as the home of world-class fast bowling, it must start now. The golden era may be over, but there is still time to write a new chapter — if the right decisions are made.

Last edited by a moderator: