shortbread

First Class Player

- Joined

- Mar 30, 2011

- Runs

- 2,783

I feel it's likely. British banks carry massive amounts on mortgage debt taken by over leveraged buyers on inflated property prices. ie. the BoE is highly reluctant to raise rates. The Fed on the other hand have clearly signalled that they are targeting 4%. If this happens the gap between the two currencies will drastically narrow.

Full article: https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/a...drop-to-parity-with-the-dollar-is-a-real-risk

Sterling’s Drop to Parity With the Dollar Is a Growing Risk

Traders fear that high inflation and weak economic growth will make it impossible to keep the UK currency from dropping further.

British politicians have a complicated relationship with the pound, which has a complicated relationship with the US dollar. Currency crises, as governments tried and failed to defend sterling against the dollar, cost Harold Wilson and John Major their premierships, and once even appeared to end the political career of Winston Churchill. Now, the notion of parity to the dollar is being openly discussed after the pound staged yet another dive, while the government of Boris Johnson struggles with a crisis in the cost of living. Can sterling’s slide be stopped, and what would be the repercussions of a pound worth less than a dollar?

It’s a serious question. Fixed at an exchange rate of more than $2 until the end of the Bretton Woods regime in 1971, the pound nearly touched parity once before, in early 1985. Higher bond yields in the booming US economy, as the aggressive monetary policy of Paul Volcker at the Federal Reserve brought inflation under control, attracted funds out of the UK.

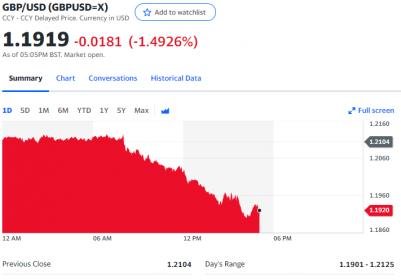

By the close of trading on Wednesday, sterling stood at $1.2251, a low it hadn’t seen since May 2020 when the first shocks of the pandemic were still being felt. Round numbers matter a lot in currency trading and so the next key psychological level will be $1.20. Since sterling’s all-time low in 1985, the pound has only dipped below this level during the worst of the political crisis over Brexit, and during the first days of the pandemic.

Those incidents centered on radical uncertainty about risks that markets find it hard to measure. This time, the crisis of confidence is driven simply by the core issue of foreign-exchange markets: traders fear that high inflation and weak economic growth will make it impossible to prop up the pound any further.

The Bank of England’s bold prediction last week that the inflation rate was heading above 10% while the economy is headed for recession came across as a “Volcker Moment.” Like Volcker at the Fed some 40 years ago, the BOE was admitting that inflation was out of control, and declaring its intent to inflict a recession on the economy to get it back under control.

The problem is that BOE’s big pronouncement had the exact opposite effect of the original Volcker Moment. To quote Marc Chandler, the chief market strategist at Bannockburn Global Forex in New York, “The BOE’s Volcker Moment crushed sterling. You have to be careful about what you wish for. They say that central banks raise rates until something breaks, and the Bank of England is saying that something’s going to break - the economy.”

The message the market has taken is that the BOE will not be able to raise rates many more times, while in the US the Fed is still sticking to the idea that it can raise rates throughout the year without killing the jobs market. The bond market shows that traders are inclined to believe the Fed, but not the BOE.

Parity against the dollar would make imports more expensive and deepen the UK’s inflation problem still further, but at this point it’s hard to see what the UK can do about it. Sterling’s fate is left in the hands of the US. Can the dollar’s strength really continue, and can the Fed really be as aggressive as it says before coming up against its own economic constraints? Many other countries around the world have heavy dollar-denominated debt, while US multinationals will dislike the way a strong dollar shrinks their overseas profits.

After Bretton Woods ended in 1971, Richard Nixon’s Treasury secretary John Connally told other finance ministers that the dollar is “our currency and your problem.” That continues to be the case.

Full article: https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/a...drop-to-parity-with-the-dollar-is-a-real-risk