Amid escalating India-Pakistan tensions, TV channels peddled misinformation and sensationalized news. But independent voices, including 8,000 X accounts, were silenced.

thediplomat.com

In early May, Maktoob Media’s newsroom was buzzing with urgency. Like many independent media outlets, its journalists were working around the clock to report on the escalating tensions between India and Pakistan. They had been sharing ground reports with their readers on X, formerly Twitter, for over two weeks.

Then, silence.

On May 8, readers told Maktoob’s founder-editor, Aslah Kayyalakkath, that the media outlet’s X account had been withheld in India. “We received no official notice or email. It was our readers who first noticed our X account had been withheld in India. That’s how we found out,” Kayyalakkath told The Diplomat.

Maktoob is an independent Indian media organization that mainly covers human rights and minority issues.

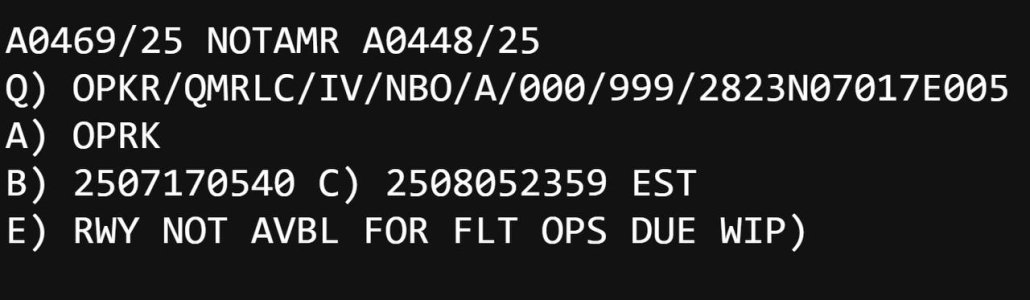

However, Maktoob wasn’t alone. In a sweeping move justified under

“national security” concerns, the Indian government directed social media platform X to block nearly 8,000 accounts—many belonging to independent journalists, regional media outlets, and activists. The order came in the aftermath of “Operation Sindoor,” which was launched by India against Pakistan and Pakistan-administered Kashmir in retaliation for the Pahalgam attack on April 22 that killed 26 tourists.

In a post, X’s Global Government Affairs team said it had “received executive orders from the Indian government requiring X to block over 8,000 accounts in India,” including “demands to block access in India to accounts belonging to international news organizations and prominent X users.”

“In most cases,” the post said, “the Indian government has not specified which posts from an account have violated India’s local laws. For a significant number of accounts, we did not receive any evidence or justification to block the accounts.”

Several of the blocked X accounts — such as those of Free Press Kashmir, Maktoob Media, BBC Urdu, The Kashmiriyat, The Wire, and the accounts of some well-known journalists, including Muzamil Jaleel of The Indian Express and Anuradha Bhasin of The Kashmir Times — have since been restored. However, the government did not make public the list of banned X accounts nor did it specify the criteria it used to ban them.

“No direct notice or explanation was provided to us by the authorities. We did not receive any prior notice or formal communication either from the Government of India or from X,” said Qazi Zaid, editor of Free Press Kashmir. “We were primarily posting factual updates, ground reports, and verified information. It’s unclear what specific content triggered the action, as no detailed reasons were shared.”

Maktoob is preparing to challenge the ban in India’s Supreme Court. The organization said it had sent emails to both the Ministry for Information and X, but received no responses. “The withholding was eventually revoked on May 17 — without informing us of the reason behind either the initial withholding or its revocation,” Kayyalakkath said.

While a warlike situation was unfolding on the ground and independent voices were being shut down, another “war” was playing out on Indian TV news channels.

The coverage of these TV channels was marked by misinformation, fake news, and sensationalized propaganda with dramatic sound effects and visuals like any action Bollywood movie. Many portrayed the Pahalgam incident in overtly communal terms. Hashtags like #PakTerror and #RevengeForPahalgam trended across platforms, aided in part by state-aligned influencers and bots.

“The TV media channels were just peddling bizarre lies and turning out bizarre stories, making claims that have no basis. Or even kind of encouraging hate rhetoric and warmongering,” said senior journalist Bhasin, who is managing editor of Kashmir Times.

In one case, Mohammad Iqbal, a resident of Indian-administered Kashmir’s Poonch who was killed in Pakistani shelling on May 7, was misrepresented by multiple TV channels as a “terrorist.” The police later refuted the claim.

News outlets like Maktoob and The Wire have extensively covered unrest in Kashmir following the Pahalgam attack in April. For Maktoob, the timing of the block wasn’t surprising or coincidental. “We were covering the India-Pakistan tensions, but we report on a wide range of issues, including human rights, marginalized communities, and current affairs,” said Maktoob’s editor. “The ban feels like a clear attempt at intimidation, a message that said: ‘We are watching you.’”

This is not the first time the Indian government has cracked down on X users. Last year, the Indian government

blocked 177 social media accounts amid the farmers’ protests, citing concerns over public order.

Disinformation by TV news channels is not recent. Sensational and false reporting has become the norm with news channels in India, especially those that are described as the “godi” (or lapdog, a reference to pro-government) media.

Kunal Majumdar, India representative for the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), told The Diplomat that silencing journalists, especially during moments of heightened geopolitical conflict, not only “undermines press freedom but also deprives the public of access to accurate and timely information when it is needed most.”

According to Bhasin, accounts were “randomly blocked.” While the blocking of accounts was not surprising, the “huge scale” at which it was done — more than 8,000 accounts were blocked at one go — was shocking.

“This is a government that wants to crush any kind of dissenting voice and any questions that are being asked. They only want to peddle a narrative that is not in sync with the ground reality, whatever it is about,” she said.

After the abrogation of Jammu and Kashmir’s special status in August 2019, Bhasin had

filed a petition in the Supreme Court challenging the information blackout in the region. The petition drew attention to how the communication blackout had paralyzed newsrooms and journalists’ work. In

2020, the Supreme Court ruled that internet access is a fundamental right. Although it did not immediately result in the restoration of internet services, Bhasin’s case became a landmark in the fight for press freedom during state-imposed censorship.

In the recent ban, her X account was withheld too. She sees the ban as a part of a broader pattern of suppressing dissent and shaping public perception through selective censorship. “I wrote to the government after I received a notification regarding the ban from X. Initially, they responded, asking me to share my identification details. I did, and then no response was received until my account was restored a few days ago.”

The peddling of propaganda and fake news by India’s major television news channels increased sharply during Operation Sindoor.

“This was absolute nonsense, absolute junk, absolute fake news, and amplification,” Bhasin said, adding that “the whole idea of such coverage is to reduce the thinking capacities of Indian citizens.”

According to Zaid, news coverage “imbalances can distort the information ecosystem. A healthy media space,” he said, “depends on the presence of diverse, fact-based voices to ensure accountability and public trust.”

Aslah said that national security and press freedom are not mutually exclusive. “If the press isn’t free, the nation and its citizens are not truly secure,” he said, stressing that “suppressing journalism undermines democratic values and transparency.”

Majumdar told The Diplomat that the CPJ does not assess the editorial standards or accuracy of mainstream media. “Our focus is on defending press freedom and ensuring the safety of journalists. That said, the absence of transparency, judicial review, and clearly defined criteria in these digital censorship actions creates an environment of fear and uncertainty — especially for independent and regional media — and raises serious concerns about the state of press freedom in India,” he said. “Unfortunately, in India, journalist safety is still not taken seriously enough — either at an institutional level or within the larger journalist fraternity.”

Critics believe that many of the affected accounts and outlets were independent voices reporting on the India-Pakistan conflict, often offering alternative perspectives or critical commentary. “Their targeting sends a chilling message and sets a dangerous precedent for freedom of expression in India,” said Majumdar.

“This isn’t just about our account being blocked,” Aslah said. “It’s about a government choosing which truths are acceptable. And about us refusing to stop telling the ones that aren’t.”

You have read

1 of your

4 free articles this month.

Enjoying this article?

Consider supporting

The Diplomat's independent journalism with a subscription.

Subscribe today to continue having full access to our extensive coverage of the Asia-Pacific.

Subscribe NowView Subscription Options

Already have an accou