An indulgent self-portrait

Reviewed by Farooq Nomani | DAWN.COM

October 14, 2011 (2 days ago)

Despite all you that may have heard about Shoaib Akhtar’s autobiography, Controversially Yours, the most startling aspect of the book is actually to be found in the pictures section. There, on the last panel, totally devoid of context and caption as if it’s the most appropriate photograph to be featured in a book about an athlete, is a picture of the fast bowler himself. Shirtless. Staring alluringly back at you, arms spread-eagle against a door frame.

There seemed to be no purpose behind this gratuitous exposure except perhaps to cater to Akhtar’s self-indulgence, and it annoyed me. I let this annoyance colour the reading of the prologue which was all too easy given that the first few pages alone contain enough Akhtar-isms to seemingly vindicate his countless detractors: the exaltation of the 100 mph mark; the over-inflated notions of his self-worth; the fear he instilled in the great batsmen of his generation.

But then I looked at that picture again, to try and comprehend its inclusion. He just stood there, half-naked, comfortably gazing at me. And suddenly, in the jarring awkwardness of the portrait, Akhtar appeared to me to be, figuratively, truly naked.

Sure, the concept behind any biography is to disclose the life of its subject matter and render it, in a sense, naked to the world. But that’s not what I mean. To me, Akhtar seemed almost vulnerable, standing there awkwardly inapposite to everything around him, doing something which probably only made sense to him. Those who it didn’t make sense to, myself included initially, would probably judge him mercilessly for it and use it as further cause to condemn him as an oddity.

That’s the story of his life, really. Or at least the way Akhtar sees it. Controversially Yours is, in classic Akhtar fashion, not about the cricket which made the man as much as it is about the man. He prioritizes ‘Akhtar the Person’ at the expense of ‘Akhtar the Cricketer’ which was an accusation constantly hurled his way during his playing days. The fact that he carried this philosophy over into his book is a shame only to the extent that we are denied insight into some of his most defining spells. The multiple and memorable decimations of Australia’s top order, his mastery over New Zealand and his conquering of South Africa – all are almost a passing reference.

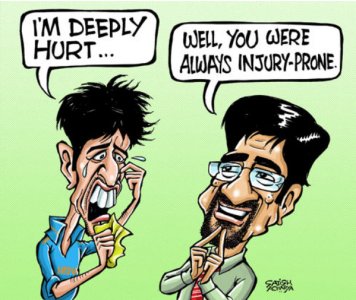

This slanted focus, however, does not hurt the book. In any event, Akhtar’s brand of fiery swing bowling lends itself more to visual presentation rather than thoughtful introspection. So he makes no qualms that this is a book in defence of himself after almost two decades of having his character denigrated and humiliated by those who never took the time to understand him. You could accuse him of playing the victim card too often. Or you could just get over yourself and read the book by holding off your cynicism and getting to know someone who, despite his various complexes and quirks, was basically just a nice guy who never meant to hurt anyone (other than Mohammad Asif, but we should let that one slide). For the two decades punctuated by occupational excellence and sustained demonisation, this is how he wishes to be remembered.

As Akhtar leads us through the story of his life, one gets the impression of a 35-year-old man who never matured past the fun-loving days of his late teens and early twenties. Akhtar’s moral compass, inter-personal relations and general world view are still guided by the principles which informed him in those early years. Luckily for Akhtar, those principles are relatively sound.

Raised modestly by a supportive family system, Akhtar was the youngest of four boys and clearly grew up as his mother’s favourite. The virtues of hard-work, persistence and constructive ambition were instilled at an early age and his family’s emphasis on his education gave him the basics of a societal understanding needed to distinguish fundamental wrongs from fundamental rights. For a guy accused of having his head in the clouds, it’s refreshing to read about the more grounded aspects of his life, like his relationship with Aziz Khan the Tongawalla and his jaunts through Rawalpindi with his old friends.

However, like any headstrong child, Akhtar exhibited an unrelenting petulance which defines him to this day. At various points of his career, Akhtar feels like he had been held back by the myopic and oppressive policies of those calling the shots and always made those responsible know how hard-done he felt in no uncertain terms. The PIA management and players, Agha Akbar, the Pakistan ‘A’ team manager, former PCB chairman Naseem Ashraf and a host of others – Akhtar never failed to treat them with as much disrespect as he felt was meted out to him.

Immature and lacking in class? Perhaps. But then Akhtar never pretends to be a saint. He admits to having a chip on his shoulder. He admits to not playing by the rules and living by his own. He admits to having a vindictive nature. He was not the easiest person to get along with but, like any child, you have to consider his upbringing to really judge where the blame lies. And from his teenage years onwards Akhtar was brought up by the unhealthiest and most twisted, dysfunctional, callous and toxic family system imaginable – the Pakistan cricketing infrastructure.

As Akhtar rightly observes, in the absence of any affordable education, the PCB becomes the default academic and intellectual learning centre for its underprivileged cricketers. Sadly, it falls damagingly below the requisite standard. We all know the culture the PCB espouses and it was the one Akhtar grew up in. Politics, back-biting, player mutinies, autocratic chairmen, short-sighted policies, favouritism, fickle captaincy and, particularly in Akhtar’s case, personal abuse. It’s a credit to Akhtar that he didn’t come out of this system as a broken husk of a man. His secret was that he refused to let the system compromise his individuality since he considered it unworthy of adapting or conforming to. This meant that he let his immaturity and petulance endure. But it also meant that he let his competitiveness and ego drive him to great heights for Pakistan cricket.

There is a bitterness at the heart of the book though, a sense of disappointment you might get from a child who just wants to be appreciated as much as the favourite son of the family. This is apparent when Akhtar observes how protectively the Australian cricket system nurtured players like Brett Lee and Shaun Tait. In Tait’s case, Cricket Australia unquestioningly accommodated his physical limitations while we vilified Akhtar for bowling in test matches with a cracked rib. The PCB and the media let the public assume he was responsible for a rape even though the true perpetrator’s identity was fiercely protected. Back in the day we all dismissed Akhtar’s complaints as frivolous and unwarranted. Little did we know that the guy just wanted to be loved.

Which is the point of his book, really. In nearly 300 pages, Akhtar attempts to convince us that he’s not as depraved as he has been made out to be. He’s just different. But then so are a lot of the eccentric friends we keep around us, those ‘characters’. Without them, life would lose a lot of its variety. So I’m thankful Akhtar didn’t compromise his individuality and disposition. Without it, Pakistan cricket would not have been as exhilarating.

Link:

http://www.dawn.com/2011/10/14/an-indulgent-self-portrait.html

.. i knw he has good record in asia but thats different from touring 2 playing first class cricket there or playing test cricket down on those dad multan wickets where once the so called great dennis cried like baby in 1980s

.. i knw he has good record in asia but thats different from touring 2 playing first class cricket there or playing test cricket down on those dad multan wickets where once the so called great dennis cried like baby in 1980s

)

)

lol

lol