Some thoughtful responses, especially the post by [MENTION=26195]DW44[/MENTION], to an interesting question.

Although overall a small factor, as mentioned in the opening post, the electoral system in Pakistan does militate against the more peripheral parties as it does anywhere, where the ‘first past the post’ system is in place. So in the 1970 elections, whilst the religious parties captured about one fifth of the vote in West Pakistan, they only garnered 5 of the 82 seats. In other elections of course, their vote share has been far less - less than 4% for example in the 1993 elections - but it could be argued that many prefer to vote for the mainstream parties because a vote for a more marginal party is thought of as a wasted vote in the ‘winner takes all’, first past the post system.

More importantly, as has already been noted on this thread, local factors and local allegiances can be crucial in determining voting patterns. When people speak of local loyalties, they are usually referring to mobilisation of voters on the basis of either the economic power of the large landlord in certain constituencies, or the kinship (‘biraderi’) attachments or pir murid relationships or just plain factional rivalry. Andrew Wilder in his book on ‘The Pakistani Voter’ has argued that the key aspect is ‘delivery’ on local development. Often people will vote for whom they think will ‘get things done’, whether it is reliable supply of water and electricity, whether it is fixing gutters, or dealing with family disputes, college applications, getting jobs for people, or arranging for criminal charges to be waived and land disputes settled.

The point is well taken, but nevertheless we should not lose sight of the fact that ideological appeals can transcend local issues. So in 1946 provincial elections, historian Ian Talbot writes that “The politics of biraderi and local power were by no means destroyed in 1946, but they had to compete, often unsuccessfully, with the Muslim League’s ideological appeals.” Even more strikingly, it is clear that in the 1970 elections in West Pakistan, the Pakistan People’s Party inspired countless individuals to vote with their conscience. The key work here is that of Phillip Jones in his study of the PPP, which argued that the vote in 1970s for the PPP “was a vote of opinion in favour of systemic change.” “It had been a vote for a party and its programme ... not for specific individuals.”

Therefore, whilst acknowledging the salience of local issues, there is more to it in explaining the failure of religious parties in capturing votes. As [MENTION=26195]DW44[/MENTION] notes, Islam is not monochromatic in Pakistan. There are many different ways of being Muslim in Pakistan. Rural constituencies dominate the electoral space in Pakistan and historically in rural Pakistan, it is not the maulvi but the pir that has tended to be more influential. The Islam of the shrine, associated with the Barelvis, is formally represented in politics through the Jamiat-ul-Ulema-i-Pakistan (JUP), but the party has never been a particularly strong institution. The Jamaat-I-Islami (JI) is the best organised of the religious parties, but its puritan message and tendency to look down on the masses has not helped its cause in winning support at the time of elections. As one of the Jamaat’s district leaders said to Anatol Lieven:

“We don’t want to rally the masses behind us, because they don’t help us. They can launch strikes and demonstrations but they are disorganized, illiterate and can’t follow our ideology or stick with our strategy. We want our party workers to be carefully screened for their education and good Muslim characters, because if we simply become like the PPP and recruit everyone, then the Jamaat is finished … We don’t care if we can’t take over the government soon as long as we keep our characters clean. Only that will help us one day to lead the people, when they realize that there is no other way of replacing the existing system.”

Deobandi interests are institutionalised through the Jamiat-ul-Ulema-i-Islam (JUI). Disdainful of the shrine based Islam practices of the Barelvis, its support has tended to electorally confined to the Frontier and Baluchistan.

Clearly then, whilst religious parties, especially the JI, can mobilise street support to agitate on certain specific causes and influence public debates on religion and morality, constructing a broad national appeal that can translate into winning a critical mass of votes and transcend religious differences is a far more difficult exercise for such partie.

Finally, as has also been noted, mainstream parties have adopted religious rhetoric and symbolism. They have not positioned themselves as avowedly ‘secular’. The language of Islam has been part of mainstream parties discourse.

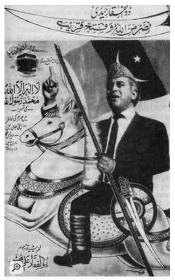

A striking example of the use of symbols with religious resonance is provided in the 1970 elections when the PPP adopted the election symbol of the

talwar. As Phillip Jones notes, ‘The sword in Islam has been a symbol both of Islamic militarism and of justice…It was precisely the kind of socio-religious symbol that appealed to the rural and urban masses and linked the PPP with the old egalitarian implies in Islam and the Punjabi folk tradition’.

From an election poster in 1970 ( from

https://www.dawn.com/news/1195863):

Clearly Pakistanis, for all the noise they make about necessity of blasphemy laws and how the identity of the state cannot be seperated from religion, will not put their money where their mouth is as they deep down don't want to live in a 6th Century state under the Jamaatis.

Clearly Pakistanis, for all the noise they make about necessity of blasphemy laws and how the identity of the state cannot be seperated from religion, will not put their money where their mouth is as they deep down don't want to live in a 6th Century state under the Jamaatis.