Imran Khan, the former playboy cricketer and would-be PM of Pakistan - The Times Interview

The Times Interview with Imran Khan - Feb 2018

Interview by Ben Judah

https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/...icketer-and-would-be-pm-of-pakistan-lswtpthpz

[Article behind pay wall]

---------------------------------

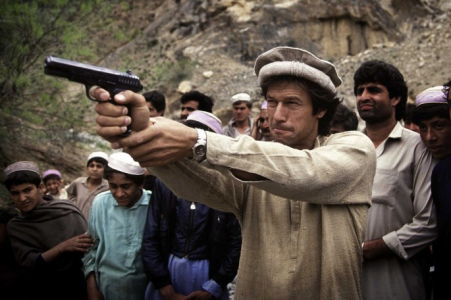

Imran Khan, the Oxford-educated former playboy cricketer, is roaring along the Pakistani campaign trail in his armoured car. Horns honk. Crowds yell. Superfans on motorbikes race after him. Thousands line the road with his flags. Hysteria grips the small Punjabi city of Mandi Bahauddin. Khan, however, is miles away. “British politics,” he intones. “It’s such a boring politics. If I had to be in British politics, after two months I would just … commit suicide.”

There is a thud on the roof. Supporters are leaping onto the Khan-mobile. But when it comes to adulation, the man who captained Pakistan to victory in the 1992 Cricket World Cup has seen it all. “British politics,” he says again, shaking his head. “The only exciting thing happening is Jeremy Corbyn making so-called outrageous statements about the status quo.”

Dressed in an immaculate white flowing shalwar kameez, nodding in satisfaction at the human tide, Khan is moments from giving a rally. A top turnout. We have just driven 3½ hours from Islamabad, knackered donkeys and dishevelled villagers clipping past the window. All the while, he has been talking about everything from God to his two sons from his former marriage to the British heiress Jemima Goldsmith, and his lost halcyon days at Keble College, Oxford. How things have changed. “Pakistani politics,” he says, smiling, “now this is such exciting politics.”

Against all expectations, the former paparazzi pin-up who once posed in his briefs for the Daily Mirror has emerged as the man both the Taliban and many in the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), Pakistan’s powerful and feared spy agency, would like to see installed as the country’s next leader. After 22 years of trying, and failing so badly he became a national joke — one newspaper ran a satirical column in his honour titled “Im the Dim” — Khan has his best shot yet at becoming prime minister. At 65, some aides whisper this may well be his last, as he leads the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) party he founded in 1996 into a fraught election to be held this July. “People laughed at me,” he frowns, as if imagining their sullen faces no longer finding “Dimran” so funny now. “But I always thought I’d win.” This, he explains, is the Imran Khan mindset. “Whatever happens, I’ll win. OK?”

Pounding his enemies, talking about winning, winning, winning, Khan reminds me of Donald Trump — and, despite his visceral loathing of the US president, whom he has labelled “ignorant and ungrateful”, it’s hard not to compare the two. Khan, like Trump, emerged from the moneyed elite, riding high on a personality cult, purporting to be the voice of every forgotten man, railing against effete liberals and the corruption and nepotism of the political class.

And just like Trump, this ageing, hair-obsessed star is accused of sexual harassment. Khan is the subject of a Pakistani #MeToo claim. His prayer beads flick faster and faster at the mention of his accuser, Ayesha Gulalai Wazir, an MP from his own party, who alleges he sent her “inappropriate” text messages and has called for a parliamentary investigation. Safe in his armoured car, armed guards riding in the pick-up truck ahead, Khan rubbishes her claims: “She’s been paid for that.” He accuses his enemies of smearing him with — guess what? Fake news. “You see what I have to put up with?”

His critics, meanwhile, denounce him as a fornicator who has never moved on from his playboy past. The author Salman Rushdie has warned he is a “dictator in waiting”. But he is no westernised darling. The Pakistanis who are the most like Khan — the English-speaking, Dubai-tripping, high-tea-drinking upper classes — are also those who are the most suspicious of him. The feeling is mutual.

Khan attacks “liberals” who support Nato’s war on the Taliban as “thirsty for blood”. “They have absolutely no idea. They sit in the drawing room. They read the English-language newspapers, which bear very little resemblance to what is real Pakistan. I promise you, they would be lost in our villages.”

Waiting to be summoned by Khan in Islamabad, I was introduced to the nickname liberals have for him: Taliban Khan — they are only half-joking. The Taliban, he has gone as far to demand, should be allowed to open offices in Pakistani cities. “American drone strikes in Pakistan must stop,” he tells me. “It’s butchery, and the true horror of it is hidden from the West.”

The man who was once married to the daughter of a Jewish billionaire now accuses Israel of “controlling the United States” and American aid of “enslaving” Pakistan. It’s hard to imagine him in leopardskin satin trousers boogieing at Annabel’s nightclub in Mayfair as he quotes the Koran at me, calling himself a “total nationalist”. The voice sounds like that of the man Tatler called “Cosmo Khan”, mixing posh Pakistani with plummy vowels, but the words don’t. “We shouldn’t be fighting other people’s wars,” he says. “Pakistan must exit the so-called war on terror.” This is his mantra.

Who is to blame for the state in which Pakistan finds itself? Khan points the finger at America. “They pushed us into a hysteria of blood-letting.” He blames the US for the rise of the Pakistani Taliban, allies of the Afghan Taliban and, like them, a ruthless, fundamentalist, ethnic Pashtun terrorist group that has repeatedly slaughtered Pakistani civilians. Khan himself was born into a wealthy Pashtun family in Lahore and never fails to speak romantically about this nearly 50m-strong “uncolonised” ethnic group.

“We ended up sending our army into our tribal areas at the request of the Americans. And our areas got devastated. We had, more or less, a civil-war situation there,” he snarls. “The aid was minuscule compared to the loss of billions and billions and the blood our country spilt.”

In 2014 the Pakistani Taliban announced that Khan should represent them in negotiations with the government. “All terrorism is politics,” he says. “All this nonsense of religious terrorism. There’s no such thing as religious terrorism. It’s politics behind it. The political injustice. Perceived injustice is why people pick up arms — throughout history.”

He says he is against all terrorism. “My tradition is of a more Sufi style of Islam,” he explains, a mystical path very different from the Taliban’s literalism.

As prime minister, would Khan break military ties and supply lines with Washington? Grinning at the crowds, he ignores the question and begins Trump-bashing instead. “He’s so boring. He’s so predictable … he’s a purely materialistic being. Whatever option makes the most money is the one he wants. He has no spiritual dimension at all.” Khan turns to me: “I wouldn’t even be in politics if I hadn’t turned towards spirituality.”

Khan seethes at both Barack Obama and Donald Trump, who is presiding over “absolute civilisational decay”. He may feel at liberty to lash out at the US, but he is terse to the point of monosyllabic on the China of Xi Jinping, who is pouring $62bn into Pakistani infrastructure. This dwarfs the $33bn Trump tweeted the US had “foolishly” handed over to Pakistan before withholding $900m in military aid recently. Beijing, for Pakistani generals, is the new Washington.

At these rallies, Khan keeps promising to “bring the China model to Pakistan” to fight poverty. But in the car he is unable to explain to me what this means beyond: “We have a lot to learn from what they did with industry.” So what is his overall plan? First, “a sovereign foreign policy”. Second, “an Islamic welfare state”. Third, “the China model”. Can he give me any details? His eyes glaze over. Even Khan’s closest aides admit the boss is not great in this department. “He’s not a strategy guy, let’s put it that way,” said Asad Umar, vice-president of Khan’s party. “He has never been in an institution, and doesn’t know how to work in an institutional setting.”

Khan’s enemies in Islamabad insist he is purely a spoiler, boosted by Pakistan’s shadowy state within a state — the network of military elites, vested interests and the ISI, which has routinely toppled governments and run the country to its designs. What does Khan say to the accusation he is the military’s man?

“What is it that the military is doing wrong that I have backed?” he snaps. Left a little uneasy at how firmly Khan shuts the question down, I try another approach. Is the military corrupt? “The military depends on the head of the military,” says Khan. “He is, in my opinion, the best head of the military we have ever had. He’s a really good guy.” This is exactly how Khan appears on TV: willing to castigate everyone, apart from Pakistan’s security men.

Worrying his prayer beads again, Khan is getting in the zone for his speech. The armoured car crawls through a forest of reaching hands and phones. “This is not normal, what’s happening,” he says, surveying the throng contentedly. “It’s one of those moments that only happens once or twice a century, when the people mobilise.” If he can win in Punjab, a stronghold of the ruling Pakistan Muslim League-N (PMLN), he can win outright. Outside the bulletproof windows, a stadium of 20,000 looms, and a sudden whimsy returns. “Staying in England would have been easy for me,” he sighs. “I could just have done some cricket-writing and made a decent living. But life would have been over.”

I first met Khan at his residence fit for a Bond villain outside Islamabad, where the walls are covered with ceremonial swords, cricket memorabilia and photos of him as a young man. I told him I’d spotted him two days earlier, in a hotel lobby in Karachi, being mobbed while he was trying to eat a piece of sushi. “Well, don’t forget,” he said when I asked how it felt to live like that, “I’m probably the most known Pakistani ever in its history.”

Once upon a time, Khan was a nobody. There were no fans to greet the 17-year-old who arrived alone into the English gloom in 1971. “That was the toughest winter of my life,” he recalls. His one-way ticket from Lahore was to play for Worcestershire County Cricket Club on a £4-a-month contract and, as he had promised his father, finish his education at the Royal Grammar School in Worcester.

“Honestly,” Khan shivers, “I’d never been away from home before and I’d never seen an English winter.” The red-brick streets. The drizzle. The pubs. It was all new to him. “I hated pubs. It had such a big impact on me,” he shudders. “I got allergic to it — the smell, the carpets and the smoking.” That first month Khan spent sitting over a glass of milk (“I have never drunk alcohol”) as the Worcestershire cricketers talked about nothing but cricket. “I thought I would go insane.”

He’d not only left behind Lahore, where his mother’s family were known as the godfathers of Lahore Cricket Club, but also a childhood spent making his four servants bat as he practised his bowling, and his social standing as a student at Aitchison College, the Eton of Pakistan.

The Worcester that Khan came to in 1971 was the kind of place where racist attacks were commonplace. He insists he never got beaten up. “But I got ‘****’-type insults on the pitch.” Struggling to make friends, he mostly ate alone. “I was shy,” he says. “You wouldn’t believe it, but I was terribly shy.”

Other RGS boys remember a quiet loner wrapped in scarves with no girlfriends. “I grew up thinking I was ugly,” Khan says. “My older sister always told me, and I accepted it in the end.” He insists he was never complimented on his looks before his success. “Success can make even the ugliest man good-looking.”

Oxford reinvented Khan. He became a socialite, somebody whose exotic looks could seduce the elite. Where he had felt alienated from the Wisden-obsessed cricketers at Worcester, he fell in love with his Oxford Blues team. “I never had that friendship again,” he says.

Khan’s university friends remember him as a hit with the ladies. “Girls would call just one after the other,” says one old acquaintance. But it didn’t feel easy to him. “I kept questioning my identity at Oxford,” Khan tells me. “And I began to see a lot of self-loathing in the [Pakistani] boys from my own school when I would meet them in London.”

Pride, shame, inferiority: a mix of emotions that left him wanting not only to win, but to trash the English and Australian cricketers who seemed unbeatable in the 1970s. “The colonial period was so close then,” he says. But there was something else driving him. Fame. He remembers wondering at Oxford what it would be like to be pop-star-famous, “like Mick Jagger or David Bowie”.

He was about to find out. His skill as a fast bowler and master of reverse swing led him to take 362 Test wickets and become captain of the Pakistan team in 1982. When Khan and Pakistan returned as World Cup victors in 1992, the throngs in Lahore were so intense, the adulation so extreme, it took them several hours to reach the city from the airport.

Driving today around the villas of Zaman Park in Lahore where Khan grew up, a void quickly becomes apparent: Khan has demolished his father’s house. His father died in 2008. He has plans to rebuild, but for the moment the plot is empty.

Aged 12, Khan went to his maternal uncle, the cricketer Javed Zaman Khan, telling him he wanted to leave home. The man Imran called “the godfather” remembers: “He was very close to his mother, and his father was not on speaking terms with his mother. There was a rift between the parents.” Imran is his mother’s son to the extent that his real surname is not Khan — his mother’s family name — but Niazi. “When I started playing cricket everyone knew me as Imran Khan because of my cousin Majid Khan,” he says. But he made no effort to rectify this misconception.

He lost his mother to cancer in 1985, and built a hospital in Lahore in her honour. He summarily dismissed his father from being the guardian of her memory as the chairman of the hospital board. Family members told me that his father’s infidelities were the cause of the rift, and for periods Imran and his father were not even on speaking terms. “I had a very formal relationship with my father,” says Khan.

What about his own sons? “I think I have to give credit to Jemima. She has been a tremendous mother to them. Because, you know, when we divorced and she returned with them to England, then I only became a part-time father.”

Khan may have now completely abandoned western dress, but he says his sons Sulaiman Isa Khan, 21, and Qasim Khan, 18, were brought up “in a bi-culture”. Both attended the exclusive Harrodian public school in the southwest London borough of Richmond with their Goldsmith cousins. “I used to see them much more than most fathers,” he says, “because all the holidays they would come and spend with me. But still it wasn’t the same as living with them. So I consider myself lucky in a sense: when they would come here, I would just drop everything and have quality time with them. But then they grew up.” When I ask if they drink alcohol, Khan does not answer — instead pivoting into bashing Pakistani “westoxified” elites.

Inside the stadium, Khan thunders against Pakistan’s ruling party as Chinese-made TV drones whizz overhead. “These are not politicians. They are the mafia! They have penetrated every institution. This is what I am up against.” The crowd roars and begins to chant for him in Urdu. I am reminded of something the vice-president of his party told me — that at these rallies he prays Khan won’t bang on about British politics. “He’s so incredibly English. I don’t know anybody else in Pakistan who will go ‘gosh’. He’ll quote Shakespeare, the Magna Carta. He’ll talk about English politics at rallies in front of half a million people, 98% of whom don’t give a rat’s *** about what happens in England. I have to say, ‘For heaven’s sake, stop quoting what happens in England.’ ”

Khan’s speech over, we are back in the car in minutes. He is pumped, hungry. We pull up at a truckers’ pit stop. “It’s just the best Pakistani food,” says Khan. No sooner is he out of the car than the screaming starts and his guards hold back another stampede. “You must try this,” he says, pointing at dishes brought in by panicked waiters. Hundreds of people are now pressing in for selfies as Khan propounds that the worst curse of British imperialism was to create an English-speaking elite isolated from the people. A man behind me is screaming, “Sultan Khan! Sultan Khan!” What’s he trying to say, I ask. “Oh, I don’t know,” says Khan, looking away, as if ever so slightly embarrassed.

Over and over he rages at “the mafias” — the politicians who keep beating him. But the more he lays into the ruling PMLN, run by the family of the former prime minister Nawaz Sharif, and the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP), controlled by the former president Asif Ali Zardari — husband of the late prime minister Benazir Bhutto — the more I realise how personal all this is. Because these politicians are all faces of the same tiny elite: Imran knew Bhutto at Oxford and played cricket with Sharif in Lahore. “Yes, it is personal,” he says. “Because I thought both of them are well off, how could they not care about what’s happening to society?”

Behind everything, there is something I find deeply aristocratic, almost feudal, about Khan. His sense of order, hierarchy and his noblesse oblige. Yet the longer I spend with him, the more estranged he seems from Imran the tabloid celeb. Something melancholic creeps over him as I ask about the 1980s, the girlfriends, the parties. He sighs. “I hardly remember anything. You know, I’ve got amnesia. I just forget all my past. ”

For a moment he stares ahead, and then he blurts out: “If I look at my life, I would have led it differently. If I had to lead it again, it’s not that I have regrets. You know, you learn from life. When I look back — it’s just that I didn’t want to get married, because international cricket and marriage never went together.”

Why? Most men would kill for that life. “Yeah, but you know what glitters is not gold. It looks from the outside very glamorous, great, but actually it’s not. It’s these transitory relationships. They’re pretty empty. You have short-term excitement, but in the long term it causes hurt and pain, which I don’t like. When I look back I don’t think it’s worth it. You know, this is how women get used, because they hope in the relationship to make the man fall in love with them and the man just uses them. It’s wrong. I just think it’s wrong.”

The more we talk, the more I feel he loathes the “westoxified” man he used to be. Parties? “I was bored with parties even in my cricketing days.” What about cricket? “Once I finished I never wanted to play again.”

He talks about how he found God. “There was this sufi who actually did change my life,” he says. “This is how I was living before. I would reach a milestone — I’m talking about cricket now — and I would think, ‘This is great.’ But then I would think, ‘No, there’s something still missing.’ And this feeling I was looking for, I couldn’t work out what it was.”

This is the Imran Khan who last month unexpectedly proposed to his faith healer, Bushra Maneka, 50. The Imran for whom something is always missing. On Twitter he asked his supporters to “pray I find personal happiness, which, except for a few years, I have been deprived of”. This sudden, some said reckless, move has horrified his operatives. Not least the fact that Maneka has not yet — unless Khan is lying, as many suspect, and has married in secret — publicly agreed to his proposal.

How many times have you been in love? “Oh,” he says, touching his chin, “I guess, tw … actually I’d rather not play that ball.”

This is the Khan that his old friends recognise: emotional, questing, believing. The sensitive and literary socialite Nusrat Jamil is one of his oldest friends from Lahore. The Khan she knows, she tells me, loves trees, animals, loved his “very religious” mother and was left in pieces by watching her die of cancer. “There’s a huge question mark and lack of clarity about him,” Jamil says. “Personally, I think there’s still a lot of confusion.”

But how can Khan the anti-western populist and Khan the playboy be the same man? “He’s not liberal, intellectually,” she says. “He may have had girlfriends, but that doesn’t make him liberal. He’s not a person who thinks in terms of a secular society, who thinks in terms of, you know, secularism and democracy. He thinks in terms of a Muslim way of living, a Muslim way of life, and that’s how he would like to live his life. That’s how he would like to run the country.”

------------

sheram tumko mager nae aati

sheram tumko mager nae aati