Exclusive: How Indian scammers built a multi-billion-dollar global fraud empire

In the world’s most populous country, where unemployment is widespread, youngsters look at scamming as just another job and not any criminal activity.

Sandeep Khatri* was quiet when he entered the rented flat in New Delhi where we had agreed to meet. The blinds were drawn, and the ceiling fan creaked as he settled into a corner of the room, adjusting the cap that hid most of his face.

It had taken

TRT World days of negotiation to get him here, on the condition that his identity be concealed, and his real workspace or photograph not be revealed.

The 27-year-old from Gurugram, a booming tech and finance city on the outskirts of Delhi, wasn’t always a scammer. Until a few years ago, he was a jobless college dropout, bouncing between low-paying gigs. “Nothing stable. Nothing dignified,” he said. “Just desperation.”

Then one night, sitting beside a friend who had landed a “tech support job,” he watched it unfold in real time: a voice calmly convincing a man that his computer had been hacked. “My friend made 80 dollars in under five minutes,” Khatri said. “That was more than I had earned in two months.”

He was hooked.

What followed was a crash course in cyber fraud: how to speak in an American accent, when to sound friendly, when to sound firm, which script to follow, and how to trigger panic.

He learned fast. Within weeks, he was pretending to be a technician from Amazon, Microsoft, or even the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) of the United States, depending on the day’s assignment.

The “office” where he works — though he refused to reveal its location — is a rented flat, he said, like the one where we met him, fitted with cheap partition walls, broadband connections, and rotating teams. “Every six months, we try to move,” he said. “You don’t stay in one place too long.”

Across India, thousands of unemployed young people like Khatri are quietly fuelling a multi-million-dollar cyber scam industry that snowballs by the day.

This burgeoning enterprise has garnered significant attention from international law enforcement agencies,

including the FBI, the federal investigation agency of the US,

and Interpol, the international criminal police organisation, leading to diplomatic challenges for New Delhi.

What was once a fringe criminal activity has evolved into a parallel economy, complete with training centres, managers, performance targets, and international revenue flows, all cloaked behind a screen and an English accent.

A scammer in Haryana’s Mewat region speaks on the phone with a victim during an extortion attempt, typically carried out during office hours. Mewat is widely known as the cyber scam capital of India (Danish Pandit).

Western nations — particularly the US, Canada and the United Kingdom — are increasingly feeling the impact of these scams, with scammers in India routinely

impersonating officials from agencies like the IRS, Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA, a US federal agency) and US Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) to extract money from foreign nationals.

In response to mounting international pressure, Indian law enforcement agencies are launching collaborative operations to combat these transnational crimes.

For instance, last year, India’s Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI), with support from the FBI and Interpol,

dismantled a sophisticated cyber-enabled financial crime network based in the National Capital Region (NCR) of India, arresting 43 individuals involved in defrauding victims of over $20 million.

Unemployment fuelling scam industry

Some 800 km away, in the India-administered Kashmir, Waseem Mir*, 28, is currently on the run, avoiding the intense crackdown on cyber fraud by the police.

Recently, authorities in the conflict-torn region launched

coordinated raids across its capital city, Srinagar and neighbouring areas, uncovering a sprawling network of over

7,200 accounts linked to scams. Several individuals connected to these operations, including some of Mir’s former associates, have been arrested.

Mir so far continues to evade capture. He spoke to

TRT World from a friend’s phone from an undisclosed location while on the run. “The police are after the entire syndicate. They are prowling on us like dogs. (sic),” he said.

His journey into cyber fraud began with a shaky call to Kansas, US, with Mir pretending to be from “Windows Support”. At the time, his palms sweated, and his voice cracked, but the American on the other end fell for it. A few hours later, $700 was wired into his digital wallet in India. “After that, I knew this was it,” Mir said. “I was done chasing job interviews.”

Mir, once an aspiring IT professional, turned to scams after repeated job rejections and seeing his peers thriving in the “calling” business. His operations now target victims in the US, UK, and Canada, tricking them into paying hundreds of dollars through fake tech support or refund scams.

“The victims are rich. We are not,” he said flatly. “To us, it feels like reverse colonialism.”

It is a rationale that echoes across India’s informal scam economy, where stories like Mir’s are not outliers but increasingly common.

A group of young scammers operates from an open field in Mewat, Haryana.

TRT World spoke to around a dozen scammers for the story who had similar tales to share.

Raju*, 24, an “employed scammer” who runs his part of the operation from a rented apartment office in suburban Delhi, said a lack of a good job led him to this work. After completing a vocational training programme from a technical institute, he struggled to find work in a saturated job market. The call centre job he landed sounded legitimate — until it didn’t.

“It was only in the second week when I saw what we were really doing — asking for remote access, pushing pop-ups, pretending to be from Microsoft — that I understood the actual nature of my work,” he said. But by then, the money had started coming in.

Raju now handles the backend: managing digital wallets, coordinating SIM card purchases, and laundering funds through mule accounts. “It’s like running a company,” he said.

Elsewhere, the industry is thriving not in city apartments, but in dusty, overlooked districts.

When

TRT World met Sultan Kareem*, 30, at his modest home in Mewat, a predominantly rural region in the north Indian state of Haryana, he was candid about how cybercrime had become a way of life in his village. Job scarcity and systemic neglect have made cybercrime an alternative economy in the entire region.

Over the past decade, the region has gained notoriety as a

national hotspot for cyber fraud, with entire networks operating across villages and involving hundreds of young, unemployed men. The area’s dense clusters of poverty, low literacy, and lack of employment have created fertile grounds for such rackets to flourish, often with little fear of consequences.

“No one in my village has ever gotten a government job,” Kareem said. “So when someone offers training, a headset, and 25,000 rupees (about $300) a month, you say ‘yes’.”

According to the India Employment Report 2024, jointly published by the International Labour Organisation (ILO) and the Institute for Human Development (IHD), individuals aged 15 to 29 account for

a staggering 83 per cent of the country’s unemployed population.

With limited access to stable jobs and few pathways into the formal economy, many young Indians are turning to online fraud, not just as a hustle, but as their primary livelihood.

For those who succeed, the rewards can be substantial.

Top scammers in his circle easily earn Indian rupees 0.1 million (about $1,200) a month — a figure that dwarfs salaries in many legitimate tech support jobs. “I have bought a luxurious car, I help run the house, and I even save a lot,” Kareem said with pride. “What else does a job need to be?”

Kareem, who calls himself an "intermediary" in the scam chain, claims to manage a team of five to six people. “One guy recently made INR 0.3 million (about $3,600) from just one victim. Some have earned up to INR 5 million (around $60,000) over a year,” he said.

A scammer looks at his phone while operating from an open field in Mewat, Haryana (Danish Pandit).

Many of these scam operations are run from indoor setups resembling makeshift call centres.

However, some scammers – particularly in rural areas like Mewat – prefer more mobile arrangements.

In these regions, it’s not uncommon to find young men perched in fields or near roadside eateries, using nothing more than a smartphone and strong cell reception to run their scams.

These open-air spots also offer a quick escape in case of a police raid, making them a tactical choice.

Organised, scalable, and invisible

Foreign nationals are typically targeted through tech support or refund scams, where Indian scammers pose as representatives from companies like Microsoft or government agencies.

They cold-call or send pop-up alerts warning victims of fake security issues. Once victims respond, the scammers gain remote access to their computers, run bogus diagnostics, and convince them to pay for unnecessary services or “refunds”.

Payments are extracted through gift cards, wire transfers, or cryptocurrency, often routed through complex networks to avoid detection.

Cybercrime expert Prabesh Choudhary, founder of Cryptus Cyber Security Pvt. Ltd, has tracked these operations for over a decade. According to him, the scam industry has evolved into an informal sector with its own hierarchy, roles, and systems of operation.

“These are not a few lone hackers,” Choudhary said. “We are talking about entire call centres, with HR departments, training modules, and supervisors.”

According to Choudhary, many of these centres masquerade as legitimate tech-startups or back-office business processing centres.

“The scams operate with a lot of precision: calling scripts are shared, psychological manipulation tactics taught, and new recruits trained to handle angry or suspicious targets. The fraudsters use VPNs, spoofed caller IDs, and different digital and cryptocurrency wallets to cover their tracks,” Choudhury said.

While the Indian authorities have occasionally cracked down on high-profile scam centres — including dramatic raids coordinated with the FBI — experts say prosecution is rare and convictions even rarer.

“There is a clear gap in cyber enforcement,” said Pavan Duggal, a Supreme Court lawyer and one of the country’s leading voices on cyberlaw. “There is no dedicated law on spam in the country, and we don't have dedicated cybercrime laws. Also, India's cybercrime conviction ratio is less than 1 per cent, which doesn’t help,” he said.

A 17-year-old scammer from India who has been involved in cyber fraud for the past three years (Danish Pandit).

Duggal explained that the problem is compounded by the absence of enforcement mechanisms and the delay in implementing key regulations. “We also have not yet implemented the

Digital Personal Data Protection Act 2023, because the government is still working on its draft rules,” he said.

The Act, once fully enforced, is expected to provide a legal framework for how personal data is collected, stored, and used — critical tools for tracing digital fraud and holding platforms accountable. Yet, even 20 months after the law was passed, the government remains in the process of finalising its operational guidelines.

In this vacuum, India has become, in Duggal’s words, “a destination hub or a fertile ground for growth of all these kinds of spam-related calls,” many of which are “manifestations of internet fraud or cyber fraud activities.”

The lack of deterrence in India’s legal system, according to Duggal, has only made matters worse, allowing scammers to operate with a sense of impunity.

“The absence of any effective convictions in the country further emboldens them. Also, the existing law makes almost all of these online crimes bailable offences, thereby giving an impression to all cyber criminals that the law is soft on them,” he said.

Duggal also advocates for urgent reform of India’s cyberlaws. “We need a dedicated Cybercrime Act, one that understands the new age of scams and has built-in protocols for rapid prosecution, victim redress, and international coordination.”

But while legal experts like Duggal call for stronger deterrence through better laws, the ease and low cost of setting up a scam operation in India continues to fuel its rapid growth.

Some fraudsters operate solo, spending as little as INR 50,000 ($600) on a second-hand laptop, a smartphone, and a stable internet connection.

But larger, more organised scam operations — often mimicking legitimate call centres—can cost upwards of INR two million ($24,000), excluding rent.

These setups may involve teams of 10 to 40 people, each assigned roles from tech support to payment processing, making the operations look startlingly professional.

A parallel economy

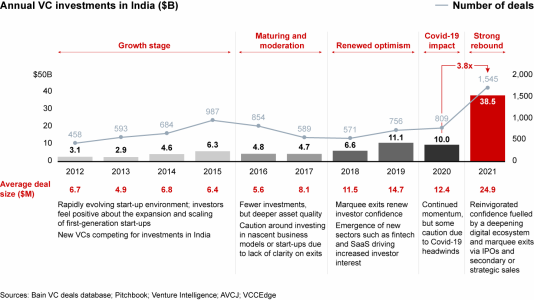

The scale of this cyber scam industry in the country is staggering.

According to data from the National Cyber Reporting Platform, which functions under the Ministry of Home Affairs, swindlers

cheated people out of 331.65 billion Indian rupees (approximately $3.88 billion) over the past four years, with INR 228.12 billion ($2.67 billion) lost in 2024 alone.

Fueled by India's digital payments boom and inconsistent cyber law enforcement, these scams have grown increasingly complex.

According to Choudhary, the cybercrime economy is now so entrenched that it mimics the structure of traditional employment sectors. “There are recruiters, resellers of data, trainers, even headhunters. Some people specialise in acquiring leads — emails, phone numbers, personal data — and sell them in bulk.”

“In just Delhi-NCR, there were more than a thousand such tech support companies running in 2017-18,” he said. “That was before COVID. After that, the modus operandi changed, but the scale didn’t shrink. They just got smarter.”

One of the scammers speaks to a victim on a call in Mewat, Haryana (Danish Pandit).

According to Choudhary, many of the scammers come from modest backgrounds and have little formal education.

“They have hardly passed the 12th standard. Some are school or college dropouts,” he said. “They do it because they don’t have another way to earn money. It’s quick. You scam someone and you get instant money — no waiting for a monthly paycheck.”

Fuelled by low entry barriers and high returns, this scam ecosystem has evolved into an informal economy that mirrors the structure of legitimate businesses.

Within this ecosystem, individuals like Kareem see themselves less as criminals and more as entrepreneurs. He describes his work in corporate terms. “We do ‘pitch meetings.’ We close sales. It is just that our product is fake,” he said with a shrug.

“But the hustle is real.”