Harsh Thakor

First Class Star

- Joined

- Oct 1, 2012

- Runs

- 3,519

- Post of the Week

- 2

Statistics maybe another criteria but the most important factor is how lethal was a pace bowler.Sheer speed is not the only factor .It is a combination of speed,with accuracy,control,movement and other variations.Infact often the slower ball is more effective than the quicker one.Some paceman were only lethal on wickets of pace and bounce while others bowled even better on slow tracks with their variations and craft.

Arguably if I had to pick a bowler for any conditions from the quickest to the slowest wicket I may pick Malcolm Marshall.True he may not have posesed Jeff Thomson or Shiaib Akhtar's sheer pace,Michael Holding's classic action and speed through the air ,was not as complete in the classical sense as Dennis Lille or Andy Roberts,did not posess the accuracy of Joel Garner and Curtly Ambrose the reverse-swinging prowess of Wasim Akram and Waqar Younus or the control of Richard Hadlee and Glen Mcgrath.However in a total package arguably Marshall surpassed them all as he posessed every component.What was extraodinary in Mashall was his ability to skid the ball and brilliantly deploy the crease like no paceman ever.Infact his skidding deliveries were often more lethal than the lerg-cutters of Dennis Lille ,the yorkers of Curtly Ambrose or the inswingers of Imran Khan.He swung the ball in and out with the same action and reading him was often like facing a googly delivery from a spinner.He created a prodigious banana swing .On the youtube I just saw his spell at Adelaide in 1984-85 where he obtained bounce from the deadest of tracks and often looked more lethal than evenn Dennis Lillee with his skidding deliveries.At a slower pace he was almost unplayable in England in 1988 disguising the movement of the ball and creating unpredictable bounce.True it was not equal to Dennis Lillee in the classical sense or not as magical in the context of pure artistry as Wasim Akram but it was a combination of classical art and magic in it's own right.Marshall posessed some deliveries in his armoury that no paceman could bowl.

Marshall's main rival was Wasim Akram.the ultimate magician amongst paceman.No fast bowler could reverse swing a ball with as much skill as Wasim who could tricks with a cricket ball that no paceman could.I wonder what seperated Wasim from Marshall.Wasim was more talented but did not have Marshall's control,accuracy and consistency.In terms of swing and movement Akram was ahead but with regards to bounce Marshall was the master.Some critiques consider Wasim Akram the more complete bowler than Malcolm Marshall with his great repertoire in addition to bounce and movement. Amongst the West Indian quickies Andy Roberts was the closest to Marshall and at his best in 1974-76 it may have been very close.Only on a bowlers paradise could Ambrose match Marshall.Marshall bowled his best spells on slower wickets like at Sydney in 1988-89.

Graham Gooch and Alan Border rate Marshall as the most difficult fast bowler they ever faced and so does Dilip Vengsarkar.The batsman of the 1970's like Sunil Gavaskar,Barry Richards and the Chappell brothers rate Andy Roberts the best.Remember Gavaskar did not face Marshall at his moral peak,while the others did not even face him.

Generally amongst experts Dennis Lillee or earlier Ray Lindwall were considered maybe even more complete but I still feel Marshall and Akram were the ultimate wizards.

Watching the youtube of spells of great fast bowlers I found no sight as menacing to behold as Marshall running in resembling a Geek God exuding fire.No pace bowler's deliveries would rear upto batsmen as visciously or with such unpredictability or seam ,swing and bounce so late.

Quoting Mike Selvey of cricinfo

Marshall's supreme excellence created debate that, from the rum shops of Oistins to the clubs and bars around the world, continues to this day. Who has been the fastest? Who is considered the best? Was it Ray Lindwall, the supreme craftsman, with complete control of swing, yorker and bouncer, or his compatriot Dennis Lillee, bristling and explosive, with a command of cut like no other of his pace before? Could it be the aristocratically haughty Imran Khan or Wasim Akram - both magicians of reverse-swing - or the deadly Waqar Younis, whose strike rate in his pomp was second to none? What about Curtly Ambrose, portrayed in calypso as The Master, the professor Andy Roberts, the inquisitor Glenn McGrath, or the surgeon that was Hadlee? Will the rampant South African, Dale Steyn, one day be so regarded?

Always the argument seems to come back to Marshall. There was nothing he seemed to lack, except perhaps height. But at 5ft 9in or so, around the same as Harold Larwood, he managed to turn that to his advantage, skidding the ball on where others might stick the ball in the pitch. He offered swing and cut, searing pace, a bouncer that seemed to climb to chin height rapidly and then level off, coming skimmingly flat; a supreme cricketing intellect that could spot flaws in an instant and smell fear, and a ruthless streak that made no concession in the pursuit of success for his team or, as in the case of Vengsarkar, occasionally of a personal vendetta.

We can start with his action. In his younger days he ran a distance, the vogue thing that had little to do with rhythm and everything to do with menace. He came in on the angle, slithering to the crease, his twinkling feet encased not in heavy bowling boots but little more than carpet slippers. Later in his career he recognised that his speed did not depend on the length of the run, but that stamina did, and he cut it down. He was open-chested at delivery, against the teaching of the manuals, but in such a neutral position that he didn't need to telegraph, through a change in action, any intention to swing the ball one way or another. And his arm was wickedly fast - twitch fast, as could be said, for example, of the golf swing of Tiger Woods.

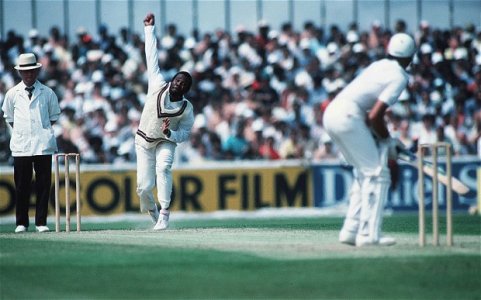

Malcolm Marshall celebrates a wicket, England v West Indies, 2nd Test, Lord's, 2nd day, June 17, 1988

What he lacked in height, Marshall made up with pace, movement and cricket intellect © PA Photos

Enlarge

Next came the tools of the trade. He swung the ball - manipulated it with hand and wrist rather than relying on a body action to do the job as many so-called swing bowlers do - outswing and inswing at will, the latter being the pace bowler's googly. He was all but impossible to read, though, for his grip remained essentially the same for both, the change coming only in a movement of the supporting thumb. Of his bouncer, we have already spoken, a potent weapon, occasionally used to excess when allowed, occasionally, for no apparent reason, against lesser batsmen, who were left bemused, not to say bruised, by the assault.

From Dennis Lillee he learned the legcutter, which he employed on dusty wickets. Against England in Gwalior, in the Nehru Cup of 1989, he produced a first ball of such startling pace to Allan Lamb - a rare England thorn in West Indian flesh during his career - that it pitched around middle stump, squaring the batsman, before jagging away and plucking out off stump. In its way it was as devastating a delivery as can ever have been bowled. He could assess the pace and productivity of a pitch, could adjust accordingly, and possessed the gift of analysis allied to instinct, which could undermine any batsman. Finally came resilience, stamina and courage.

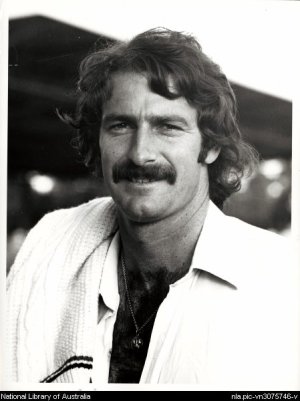

Almost invariably the debate returns to the two figures: Lillee, the prototype modern fast bowler, and Marshall. Most would admit little more than a coat of varnish between the pair. None would quibble if the other got the nod. But Lillee had no record on the heartbreaking pitches of the subcontinent, in the days before reverse-swing made their abrasiveness into a virtue, not playing a single Test in India, and managing only three wickets in as many Tests on desperate surfaces in Pakistan in 1979-80. Marshall succeeded in Pakistan and in India. Both were complete fast bowlers. When they buried Marshall though, they interred the epitome of sustained fast-bowling excellence. He really was the best of the very best.

Marshall's supreme excellence created debate that, from the rum shops of Oistins to the clubs and bars around the world, continues to this day. Who has been the fastest? Who is considered the best? Was it Ray Lindwall, the supreme craftsman, with complete control of swing, yorker and bouncer, or his compatriot Dennis Lillee, bristling and explosive, with a command of cut like no other of his pace before? Could it be the aristocratically haughty Imran Khan or Wasim Akram - both magicians of reverse-swing - or the deadly Waqar Younis, whose strike rate in his pomp was second to none? What about Curtly Ambrose, portrayed in calypso as The Master, the professor Andy Roberts, the inquisitor Glenn McGrath, or the surgeon that was Hadlee? Will the rampant South African, Dale Steyn, one day be so regarded?

Always the argument seems to come back to Marshall. There was nothing he seemed to lack, except perhaps height. But at 5ft 9in or so, around the same as Harold Larwood, he managed to turn that to his advantage, skidding the ball on where others might stick the ball in the pitch. He offered swing and cut, searing pace, a bouncer that seemed to climb to chin height rapidly and then level off, coming skimmingly flat; a supreme cricketing intellect that could spot flaws in an instant and smell fear, and a ruthless streak that made no concession in the pursuit of success for his team or, as in the case of Vengsarkar, occasionally of a personal vendetta.

We can start with his action. In his younger days he ran a distance, the vogue thing that had little to do with rhythm and everything to do with menace. He came in on the angle, slithering to the crease, his twinkling feet encased not in heavy bowling boots but little more than carpet slippers. Later in his career he recognised that his speed did not depend on the length of the run, but that stamina did, and he cut it down. He was open-chested at delivery, against the teaching of the manuals, but in such a neutral position that he didn't need to telegraph, through a change in action, any intention to swing the ball one way or another. And his arm was wickedly fast - twitch fast, as could be said, for example, of the golf swing of Tiger Woods.

Malcolm Marshall celebrates a wicket, England v West Indies, 2nd Test, Lord's, 2nd day, June 17, 1988

What he lacked in height, Marshall made up with pace, movement and cricket intellect © PA Photos

Enlarge

Next came the tools of the trade. He swung the ball - manipulated it with hand and wrist rather than relying on a body action to do the job as many so-called swing bowlers do - outswing and inswing at will, the latter being the pace bowler's googly. He was all but impossible to read, though, for his grip remained essentially the same for both, the change coming only in a movement of the supporting thumb. Of his bouncer, we have already spoken, a potent weapon, occasionally used to excess when allowed, occasionally, for no apparent reason, against lesser batsmen, who were left bemused, not to say bruised, by the assault.

From Dennis Lillee he learned the legcutter, which he employed on dusty wickets. Against England in Gwalior, in the Nehru Cup of 1989, he produced a first ball of such startling pace to Allan Lamb - a rare England thorn in West Indian flesh during his career - that it pitched around middle stump, squaring the batsman, before jagging away and plucking out off stump. In its way it was as devastating a delivery as can ever have been bowled. He could assess the pace and productivity of a pitch, could adjust accordingly, and possessed the gift of analysis allied to instinct, which could undermine any batsman. Finally came resilience, stamina and courage.

Almost invariably the debate returns to the two figures: Lillee, the prototype modern fast bowler, and Marshall. Most would admit little more than a coat of varnish between the pair. None would quibble if the other got the nod. But Lillee had no record on the heartbreaking pitches of the subcontinent, in the days before reverse-swing made their abrasiveness into a virtue, not playing a single Test in India, and managing only three wickets in as many Tests on desperate surfaces in Pakistan in 1979-80. Marshall succeeded in Pakistan and in India. Both were complete fast bowlers. When they buried Marshall though, they interred the epitome of sustained fast-bowling excellence. He really was the best of the very best.

Arguably if I had to pick a bowler for any conditions from the quickest to the slowest wicket I may pick Malcolm Marshall.True he may not have posesed Jeff Thomson or Shiaib Akhtar's sheer pace,Michael Holding's classic action and speed through the air ,was not as complete in the classical sense as Dennis Lille or Andy Roberts,did not posess the accuracy of Joel Garner and Curtly Ambrose the reverse-swinging prowess of Wasim Akram and Waqar Younus or the control of Richard Hadlee and Glen Mcgrath.However in a total package arguably Marshall surpassed them all as he posessed every component.What was extraodinary in Mashall was his ability to skid the ball and brilliantly deploy the crease like no paceman ever.Infact his skidding deliveries were often more lethal than the lerg-cutters of Dennis Lille ,the yorkers of Curtly Ambrose or the inswingers of Imran Khan.He swung the ball in and out with the same action and reading him was often like facing a googly delivery from a spinner.He created a prodigious banana swing .On the youtube I just saw his spell at Adelaide in 1984-85 where he obtained bounce from the deadest of tracks and often looked more lethal than evenn Dennis Lillee with his skidding deliveries.At a slower pace he was almost unplayable in England in 1988 disguising the movement of the ball and creating unpredictable bounce.True it was not equal to Dennis Lillee in the classical sense or not as magical in the context of pure artistry as Wasim Akram but it was a combination of classical art and magic in it's own right.Marshall posessed some deliveries in his armoury that no paceman could bowl.

Marshall's main rival was Wasim Akram.the ultimate magician amongst paceman.No fast bowler could reverse swing a ball with as much skill as Wasim who could tricks with a cricket ball that no paceman could.I wonder what seperated Wasim from Marshall.Wasim was more talented but did not have Marshall's control,accuracy and consistency.In terms of swing and movement Akram was ahead but with regards to bounce Marshall was the master.Some critiques consider Wasim Akram the more complete bowler than Malcolm Marshall with his great repertoire in addition to bounce and movement. Amongst the West Indian quickies Andy Roberts was the closest to Marshall and at his best in 1974-76 it may have been very close.Only on a bowlers paradise could Ambrose match Marshall.Marshall bowled his best spells on slower wickets like at Sydney in 1988-89.

Graham Gooch and Alan Border rate Marshall as the most difficult fast bowler they ever faced and so does Dilip Vengsarkar.The batsman of the 1970's like Sunil Gavaskar,Barry Richards and the Chappell brothers rate Andy Roberts the best.Remember Gavaskar did not face Marshall at his moral peak,while the others did not even face him.

Generally amongst experts Dennis Lillee or earlier Ray Lindwall were considered maybe even more complete but I still feel Marshall and Akram were the ultimate wizards.

Watching the youtube of spells of great fast bowlers I found no sight as menacing to behold as Marshall running in resembling a Geek God exuding fire.No pace bowler's deliveries would rear upto batsmen as visciously or with such unpredictability or seam ,swing and bounce so late.

Quoting Mike Selvey of cricinfo

Marshall's supreme excellence created debate that, from the rum shops of Oistins to the clubs and bars around the world, continues to this day. Who has been the fastest? Who is considered the best? Was it Ray Lindwall, the supreme craftsman, with complete control of swing, yorker and bouncer, or his compatriot Dennis Lillee, bristling and explosive, with a command of cut like no other of his pace before? Could it be the aristocratically haughty Imran Khan or Wasim Akram - both magicians of reverse-swing - or the deadly Waqar Younis, whose strike rate in his pomp was second to none? What about Curtly Ambrose, portrayed in calypso as The Master, the professor Andy Roberts, the inquisitor Glenn McGrath, or the surgeon that was Hadlee? Will the rampant South African, Dale Steyn, one day be so regarded?

Always the argument seems to come back to Marshall. There was nothing he seemed to lack, except perhaps height. But at 5ft 9in or so, around the same as Harold Larwood, he managed to turn that to his advantage, skidding the ball on where others might stick the ball in the pitch. He offered swing and cut, searing pace, a bouncer that seemed to climb to chin height rapidly and then level off, coming skimmingly flat; a supreme cricketing intellect that could spot flaws in an instant and smell fear, and a ruthless streak that made no concession in the pursuit of success for his team or, as in the case of Vengsarkar, occasionally of a personal vendetta.

We can start with his action. In his younger days he ran a distance, the vogue thing that had little to do with rhythm and everything to do with menace. He came in on the angle, slithering to the crease, his twinkling feet encased not in heavy bowling boots but little more than carpet slippers. Later in his career he recognised that his speed did not depend on the length of the run, but that stamina did, and he cut it down. He was open-chested at delivery, against the teaching of the manuals, but in such a neutral position that he didn't need to telegraph, through a change in action, any intention to swing the ball one way or another. And his arm was wickedly fast - twitch fast, as could be said, for example, of the golf swing of Tiger Woods.

Malcolm Marshall celebrates a wicket, England v West Indies, 2nd Test, Lord's, 2nd day, June 17, 1988

What he lacked in height, Marshall made up with pace, movement and cricket intellect © PA Photos

Enlarge

Next came the tools of the trade. He swung the ball - manipulated it with hand and wrist rather than relying on a body action to do the job as many so-called swing bowlers do - outswing and inswing at will, the latter being the pace bowler's googly. He was all but impossible to read, though, for his grip remained essentially the same for both, the change coming only in a movement of the supporting thumb. Of his bouncer, we have already spoken, a potent weapon, occasionally used to excess when allowed, occasionally, for no apparent reason, against lesser batsmen, who were left bemused, not to say bruised, by the assault.

From Dennis Lillee he learned the legcutter, which he employed on dusty wickets. Against England in Gwalior, in the Nehru Cup of 1989, he produced a first ball of such startling pace to Allan Lamb - a rare England thorn in West Indian flesh during his career - that it pitched around middle stump, squaring the batsman, before jagging away and plucking out off stump. In its way it was as devastating a delivery as can ever have been bowled. He could assess the pace and productivity of a pitch, could adjust accordingly, and possessed the gift of analysis allied to instinct, which could undermine any batsman. Finally came resilience, stamina and courage.

Almost invariably the debate returns to the two figures: Lillee, the prototype modern fast bowler, and Marshall. Most would admit little more than a coat of varnish between the pair. None would quibble if the other got the nod. But Lillee had no record on the heartbreaking pitches of the subcontinent, in the days before reverse-swing made their abrasiveness into a virtue, not playing a single Test in India, and managing only three wickets in as many Tests on desperate surfaces in Pakistan in 1979-80. Marshall succeeded in Pakistan and in India. Both were complete fast bowlers. When they buried Marshall though, they interred the epitome of sustained fast-bowling excellence. He really was the best of the very best.

Marshall's supreme excellence created debate that, from the rum shops of Oistins to the clubs and bars around the world, continues to this day. Who has been the fastest? Who is considered the best? Was it Ray Lindwall, the supreme craftsman, with complete control of swing, yorker and bouncer, or his compatriot Dennis Lillee, bristling and explosive, with a command of cut like no other of his pace before? Could it be the aristocratically haughty Imran Khan or Wasim Akram - both magicians of reverse-swing - or the deadly Waqar Younis, whose strike rate in his pomp was second to none? What about Curtly Ambrose, portrayed in calypso as The Master, the professor Andy Roberts, the inquisitor Glenn McGrath, or the surgeon that was Hadlee? Will the rampant South African, Dale Steyn, one day be so regarded?

Always the argument seems to come back to Marshall. There was nothing he seemed to lack, except perhaps height. But at 5ft 9in or so, around the same as Harold Larwood, he managed to turn that to his advantage, skidding the ball on where others might stick the ball in the pitch. He offered swing and cut, searing pace, a bouncer that seemed to climb to chin height rapidly and then level off, coming skimmingly flat; a supreme cricketing intellect that could spot flaws in an instant and smell fear, and a ruthless streak that made no concession in the pursuit of success for his team or, as in the case of Vengsarkar, occasionally of a personal vendetta.

We can start with his action. In his younger days he ran a distance, the vogue thing that had little to do with rhythm and everything to do with menace. He came in on the angle, slithering to the crease, his twinkling feet encased not in heavy bowling boots but little more than carpet slippers. Later in his career he recognised that his speed did not depend on the length of the run, but that stamina did, and he cut it down. He was open-chested at delivery, against the teaching of the manuals, but in such a neutral position that he didn't need to telegraph, through a change in action, any intention to swing the ball one way or another. And his arm was wickedly fast - twitch fast, as could be said, for example, of the golf swing of Tiger Woods.

Malcolm Marshall celebrates a wicket, England v West Indies, 2nd Test, Lord's, 2nd day, June 17, 1988

What he lacked in height, Marshall made up with pace, movement and cricket intellect © PA Photos

Enlarge

Next came the tools of the trade. He swung the ball - manipulated it with hand and wrist rather than relying on a body action to do the job as many so-called swing bowlers do - outswing and inswing at will, the latter being the pace bowler's googly. He was all but impossible to read, though, for his grip remained essentially the same for both, the change coming only in a movement of the supporting thumb. Of his bouncer, we have already spoken, a potent weapon, occasionally used to excess when allowed, occasionally, for no apparent reason, against lesser batsmen, who were left bemused, not to say bruised, by the assault.

From Dennis Lillee he learned the legcutter, which he employed on dusty wickets. Against England in Gwalior, in the Nehru Cup of 1989, he produced a first ball of such startling pace to Allan Lamb - a rare England thorn in West Indian flesh during his career - that it pitched around middle stump, squaring the batsman, before jagging away and plucking out off stump. In its way it was as devastating a delivery as can ever have been bowled. He could assess the pace and productivity of a pitch, could adjust accordingly, and possessed the gift of analysis allied to instinct, which could undermine any batsman. Finally came resilience, stamina and courage.

Almost invariably the debate returns to the two figures: Lillee, the prototype modern fast bowler, and Marshall. Most would admit little more than a coat of varnish between the pair. None would quibble if the other got the nod. But Lillee had no record on the heartbreaking pitches of the subcontinent, in the days before reverse-swing made their abrasiveness into a virtue, not playing a single Test in India, and managing only three wickets in as many Tests on desperate surfaces in Pakistan in 1979-80. Marshall succeeded in Pakistan and in India. Both were complete fast bowlers. When they buried Marshall though, they interred the epitome of sustained fast-bowling excellence. He really was the best of the very best.

Last edited:

in his early part. Complete destruction.

in his early part. Complete destruction. )

)